In the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, segregation is a deprivation of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

By consolidated opinion, the Court reviewed four state cases in which African-American minors sought admission to the public schools of their community on a non-segregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by Caucasian children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the minors of the equal protection of the laws. In each case, except the Delaware case, the district court denied relief to the minors on the "separate but equal" doctrine announced by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. The minors contended that the public schools were not equal and could not be made equal, thereby denying them equal protection of the law.

Does the segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprive the children of educational opportunities in violation of the Equal Protection Clause?

Yes

The Court held that in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Segregation was a denial of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

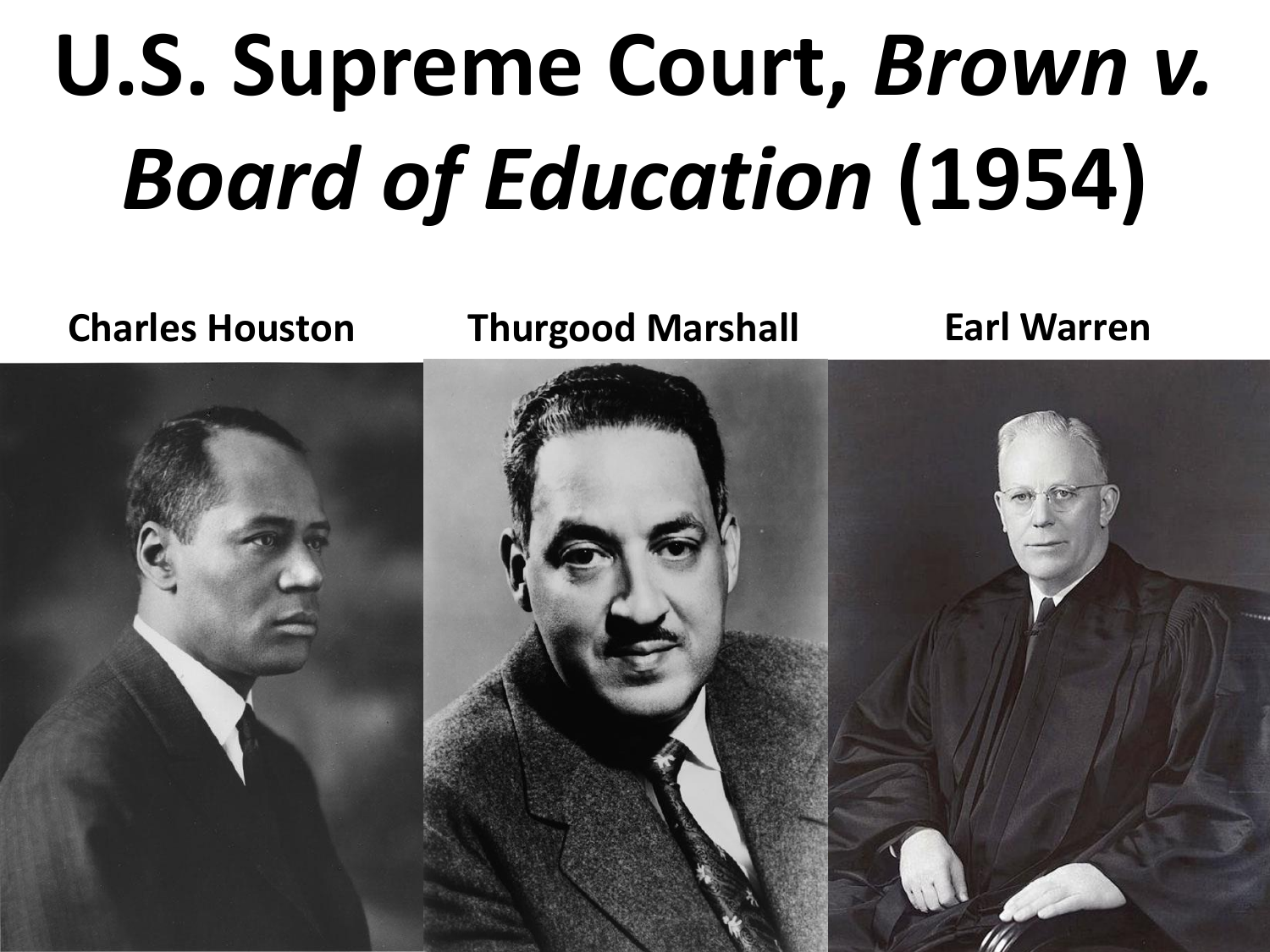

Charles Houston

Charles HoustonOn May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment and was therefore unconstitutional.

Jim Crow laws were a collection of state and local statutes that legalized racial segregation. Named after a Black minstrel show character, the laws—which existed for about 100 years, from the post-Civil War era until 1968—were meant to marginalize African Americans by denying them the right to vote, hold jobs, get an education or other opportunities. Those who attempted to defy Jim Crow laws often faced arrest, fines, jail sentences, violence and death.

Though the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board didn’t achieve school desegregation on its own, the ruling (and the steadfast resistance to it across the South) fueled the nascent civil rights movement in the United States.

In 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus. Her arrest sparked the Montgomery bus boycott and would lead to other boycotts, sit-ins and demonstrations (many of them led by Martin Luther King Jr.), in a movement that would eventually lead to the toppling of Jim Crow laws across the South.

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, backed by enforcement by the Justice Department, began the process of desegregation in earnest. This landmark piece of civil rights legislation was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

In 1976, the Supreme Court issued another landmark decision in Runyon v. McCrary, ruling that even private, nonsectarian schools that denied admission to students on the basis of race violated federal civil rights laws.

By overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine, the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education had set the legal precedent that would be used to overturn laws enforcing segregation in other public facilities. But despite its undoubted impact, the historic verdict fell short of achieving its primary mission of integrating the nation’s public schools.

Today, more than 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education, the debate continues over how to combat racial inequalities in the nation’s school system, largely based on residential patterns and differences in resources between schools in wealthier and economically disadvantaged districts across the country.